The Problem of the Oriental Gaze

Dispatches from childhood readings

I came up with the idea for today’s newsletter seven months ago. It was something like a natural progression in the Connected Books series. I had just finished imbibing Compass by Mathias Enard and my mind was vaulting over his comprehensive treatment of the Oriental gaze. Briefly, the musicologist Frank Ritter, an insomniac, recollects his travels across the Middle East, a stream-of-consciousness ballad of music, history, popular culture, warfare, literature, and art. Of course, the words “Orient” and “Far East” aren’t used in scholarly circles anymore. The homogenization of cultures from Japan to Lebanon in itself is problematic. But these umbrella terms are still used daily to denote the exoticism that surged in the heyday of colonial administration. Not anymore (oh, wait, let’s not be hasty on that part, neocolonialism is a thing).

Edward Said’s influence on Enard’s work was evident but it felt surprisingly refreshing to read a fiction that encompassed the last three decades of history surrounding the titular problem. In one of my several short reviews of the book, I wrote,

Of the Western gaze at the Orient, the Europeans with their hotels and khaki pants and souk strolls while the Assad regime bulldozes the very history these people dug up a century ago. The twisted perversion and stupidity of confusing history as tainted just because it was touched by foreign hands. That's my line, not the author's.

But the keystone of the book rested in what Enard calls “The violence of imposed identities." Enard is showing us the fact that the West classifies people so easily with ethnicities and religions by looking at their names. That easy classification is what brings us here.

Today, I come to you with a heavy heart and a few books. I had to rethink the books I wanted to talk about for this topic but the essence remains the same. This isn’t a list of what one must, should, can, or have to do read during these times. God forbid, succumb to the dreaded W-word. Proselytizing is harmful, not remedial. And what remedy can a person provide in this multifactorial catastrophe that is the result of a domino effect of minor and major historical events? But I have my story. I wonder if it is familiar to you. Perhaps not. If it is, did you read some of these books as a child or a teenager? Did other books influence your views about the Far East and the Middle East? Were they primarily by Western writers? Were they translations? And how did they shape your ideas surrounding the Orient? Something to think about.

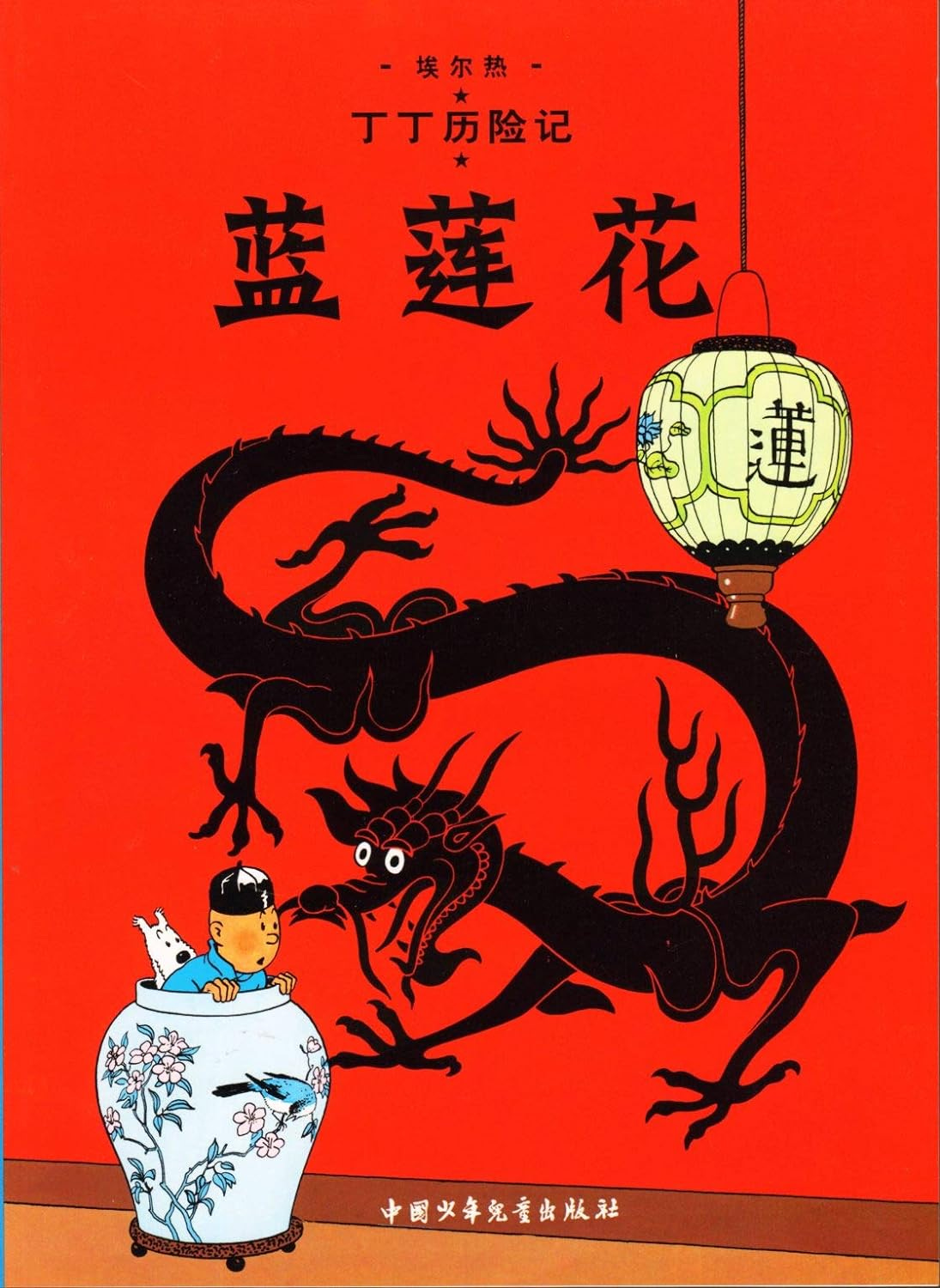

I read The Blue Lotus in a Bengali children’s magazine called Anandamela. I had just started learning Bangla that year and comics were easier to read than prose. Bengali was the first Indian language into which Tintin was translated from the original French in 1975. Hergé’s ligne claire art fascinated me; the sharp unbroken lines, zero hatching, realistic architecture, cartoonish characters, and bright colors.

The Blue Lotus was inspired by Chang Chong-Jen, an artist and Hergé’s friend at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. Hergé was influenced by Chinese ink drawings which he merged with his European sensibilities in creating art that depicted the plight of the Chinese under Japanese colonial rule. And it worked. Hergé, learning the tropes of political propaganda, created subtle changes in how the Chinese characters looked different from the oppressive Japanese. The character, Chang, Tintin’s friend was based on Chong-Jen himself. Chang, with his watermelon seed eyes, looked no different from Tintin or the other Western characters. But the Japanese officers have that characteristic squinted eye that makes them foreign or the “other”. Even as a kid, I noticed these differences. Incidentally, The Blue Lotus was also my introduction to Chinese calligraphy, communist history, the relationship between power and corruption, occupation by foreign powers, and the opium trade.

I love Tintin. Haddock. Snowy. Calculus. The whole universe. At once aesthetically pleasing and deeply flawed with racial problems, the comics remain an early influence in my understanding of various cultures.

There’s a huge Higginbothams bookstore at the Chennai Central Railway Station. We were on a school trip and huddled inside the shop before our train arrived. I pulled a book from the shelf with a single-word title. She by H. Rider Haggard. The blurb had these keywords: Africa, jungle, adventure, Victorian, scholar, queen. Of course, I bought it with the meagre pocket money I was given for the whole trip. I finished reading it on the train ride and have never read it again.

Two Victorian scholars, Horace Holly (a professor at Cambridge) and Leo Vincey (his ward), embark on a journey to Zanzibar where they meet the Amahagger natives who are ruled by a mysterious white queen named Ayesha, called “She” or "She-who-must-be-obeyed". Ayesha possesses supernatural powers of mind reading and knows the secret of immortality that we associate with vampires. She is the embodiment of British civilization against the savagery and barbarism of dark-skinned natives. Her being the tyrant female ruler is a key reminder of the erotic femme fatales like Homer’s Circe or Shakespeare’s Cleopatra. Haggard was writing during a time when Queen Victoria was already on the throne for fifty years. All this was a little too much for my teenage mind. Not to mention there was violence, forced rituals, and a man-eating “hot pot” event that raised my hair. I was expecting another Around the World in 80 Days but it wasn’t. Female domination and authority are wrapped in an imperialist meshwork and hard to segregate into progressive threads if any.

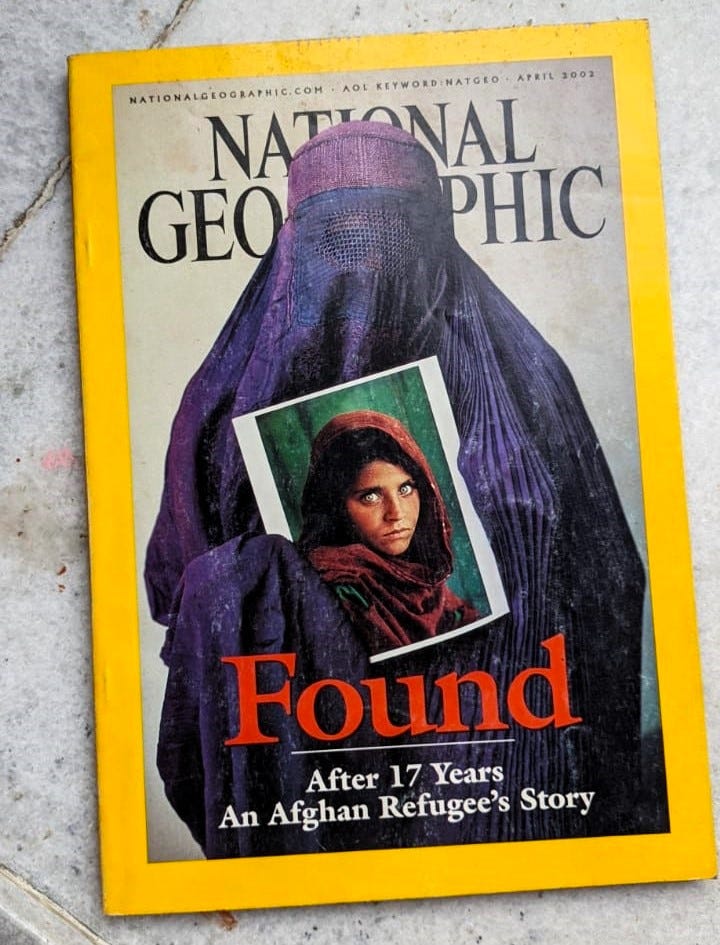

In 1984, photographer Steve McCurry travelled to Nasir Bagh, Pakistan, where Afghan refugees were fleeing the Soviet-Afghan war. While documenting the effects of the war, he took what was to become one of the most iconic cover photographs for National Geographic. The face that launched a thousand war relief campaigns and was plastered across Amnesty’s advertisements. Sharbat Gula, the Afghan Girl, became an emblem of the Afghan conflict and suffering. But the girl who was so recognizable to the mainstream media was unknown to the photographer. So, the team went back to Afghanistan when they realised the refugee camps were being closed. They found Sharbat, now 30 years old, and identified her using iris recognition. National Geographic aired a special programme Search for the Afghan Girl in March 2002 about Gula’s current life.

I watched the National Geographic programme with great interest. I tracked down the 2002 edition of the magazine when I went to college. My sympathy was aligned with what I read and saw on the television and the news I consumed. But I also realized this sympathy comes at a price. It’s secondhand. Diluted over thousands of pixels. A compassion that sometimes seems false. I have come to terms with the soft voyeurism that comes with the consumption of haunting images now. Wartime photography is essential. It’s our collective history. But I leave you with Sontag’s views on the complicated nature of photography.

“To photograph people is to violate them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.”

― Susan Sontag, On Photography

2002: One year after that event. Over the past couple of weeks, I confessed to a few close friends that I was feeling the same tectonic shift that I felt twenty-two years ago. Western powers are confused as to what to do about the Oriental problem. A subliminal horror repeating itself. This time with more cameras and more images.

I remember reading Aladdin while I was in Benaras (Varanasi) for the holidays. It was cold. Christmastime. I disliked the holy city because of the crowd, the noise, and the frequent food poisoning. I fell sick every time I visited this place. And I remember imagining the market scenes from Aladdin as I entered the dingy market lane leading to the Kashi Vishwanath temple. Damp and smelling of rabri and jalebis. I looked around for a magic lamp or any lamp in the shops selling puja paraphernalia. A genie to fly me out of this claustrophobic lane.

Such was my introduction to the world of djinns (jinns or genies). Disney has a lot to answer for the way it entrenched the images of Oriental magic and folklore. The Jasmine dresses (I never wanted one but the diadem, yes, I did want that). The bazaars. The magic carpet! The wish-fulfiling spirits. I grew up with a penchant for mythological and supernatural studies. Never found the lamp or the Jasmine diadem. However, I quickly assimilated the complicated nature of a monotheistic religion, not just Islam, through my studies. For example, a djinn is not strictly an Islamic concept but is found in many pre-Islamic pagan beliefs. Winged deities existed in the Assyrian culture seen in reliefs found in Dur-Sharrukin, modern-day Iraq.

The other day I saw Three Thousand Years of Longing. A maximalist movie about love, longing, and desire set against the tale of a djinn, played by Idris Elba, and a fiercely independent English scholar, played by Tilda Swinton. A touch of the problem emerged through the story. The celebration of the grandeur and exoticism of the Orient set against the cold and harsh minimalism of the modern world. And yet the movie was successful in capturing the essence of everlasting love, a form that travels on magic carpets, is fearful of trickster djinns, infused in perfumes, and lives inside poetry. I can’t complain about that. But I am mindful of the discomforts of the narrative and my childhood influences.

I love this piece! One thing that is salient to me, reading it, is how we can learn about other cultures etc even if the sources are problematic. I too learned a lot about East Asian cultures and philosophies as well as material culture through Tintin. As a Belgian growing up near Brussels it was impossible not to be influenced/know about Tintin. Hergé had such a big influence on me he even influenced by drawing style cf https://global.oup.com/academic/product/philosophy-illustrated-9780190080532

We often demand perfect alignment with norms in our fictions, but especially older ones just don't confirm to that. Tintin is an example. The anti-Japanese sentiment in the books is pretty bad and the books on Africa (to my recollection I could not reread them) are terrible. Hergé also admitted later to ignorance in e.g., the books where the descendants of the Inca cannot predict a solar eclipse, which of course they would've had the cultural knowledge to. So he messed up some times and he did acknowledge it. At the same time, Tintin opened for me worlds like China and Tibet that I otherwise, as a kid, would not have had an entry to.

I was particularly struck by "I have come to terms with the soft voyeurism that comes with the consumption of haunting images now." I've been thinking so much about recent events and their report over social media but hadn't found the right words for it. Here they are.

I too was around and cognizant in 2001. I had skipped school because I wasn't feeling well, so I was at home having breakfast with my mother when all TV stations shifted to showing NYC. I don't think I'll ever forget those images. How much has changed, and how little has changed...