The Ecophilosophy of Nausicaä: Part I

Hayao Miyazaki, environmentalism, fungal diseases, and monsters

Consider the picture above. A giant, sleepy, fourteen-eyed, scaly, ashen-blue trilobite-like creature. A girl holding what looks like a glass shell but seems to be one of those eyes stands on top of the arthropod. Eventually, it turns out to be an empty exoskeleton. They are in a deep stalactite-adorned cavern surrounded by a tuberous, spinous, pendulous, stellate, bulbous, fern-like assortment of plants, possibly fungi, devoid of green, no sign of chlorophyll, a pigment, a color, taken so for granted, we seldom imagine what a world without living plants would look like.

Technically, Nausicaä isn’t a Ghibli movie. It was never meant to be one. Hayao Miyazaki began serializing the Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982) manga in the February issue of Tokuma Shoten Publishing’s Animage magazine. Animage agreed to bankroll the manga into a feature film and roped in Isao Takahata as the producer. Miyazaki created the manga series over 12 years. But the movie took Japan by storm and its success led to the formation of Ghibli Studios in 1985. Nausicaä remains one of the most visually rich and structurally fascinating movies depicting themes of anti-war pacifism, environmentalism, and humankind’s relationship with nature. The movie is pale compared to the seven-volume manga with sprawling universes and plots. But the movie is nonetheless an important milestone in animation history.

After all, it is hard work to bring a film inside my head to life. Each drawing is just one frame, and within that one frame is a lot of fantasy.

-Starting Point: 1979–1996) by Hayao Miyazaki

Premise and Inspiration

One thousand years have passed since the Seven Days of Fire in which biomechanical agents called God Warriors incinerated life on Earth ending the industrialized world as we know it today. The ecocide gave rise to a toxic forest called the Sea of Decay swarming with giant mutant insects of all shapes and forms. One of these is the giant glass-eyed insect featured above called Ohmu. The noxious miasma and harmful spores from the poisonous plants force surviving humans to wear masks while venturing near the forest (the essay writer is a mask-wearing AQI-checking human with respiratory issues). It has been written elsewhere that the mercury poisoning of Minamata Bay sparked Miyazaki’s inspiration for this story.

Isolated human communities live in places still free from the clutches of the toxic forest. Our protagonist, Nausicaä, is the princess from the Valley of Wind, a place nestled between cliff faces where strong winds keep the spores at bay. The people have an agrarian lifestyle, living in houses inspired by medieval architecture, and harnessing wind via windmills and ingenious technologies that feel like solarpunk; a sci-fi genre where ecological utopias celebrate the harmony between nature and technology.

Miyazaki was inspired by the Phaeacian princess, Nausicaä or Nausikaa, who appears in Homer's Odyssey. She tended to Odysseus’s injuries while he was stranded on an island. The other character who inspired Miyazaki was a Japanese heroine from a collection of short stories from the eleventh century known as Tsutsumi chū-nagon monogatari (Tales of the Tsutsumi Middle Counselor). She was a princess who loved insects and loved exploring in nature like watching caterpillars turn into butterflies. This was quite different to the taboos surrounding girls like staining their teeth black (ohaguro, お歯黒) and shaving their eyebrows during Japan’s Heian period. A merging of the rebellious Japanese princess and tenderness of Homer’s character gave rise to the empathetic, eco-conscious Nausicaä of our movie.

Fun fact: I learned about ohaguro from the recent anime series called Blue Eye Samurai. The color black, or kuro, is traditionally a masculine color in Japan. It has often been used for the samurai class and ohaguro was practced as a token of loyalty for the devotion of the samurais towards their masters. Eventually, young women started blackeining their teeth to enhance beauty and attract spouses.

The bucolic life in the Valley is disrupted by a huge airship from the Western kingdom of Tolmekia which crashes near the fields. The people of the Valley discover that the ship is carrying the newly discovered and probably the last remaining God Warrior. Thus begins warfare between the Tolmekians and the kingdom of Pejite (where the God Warrior was initially discovered underground). Whoever controls the Warrior can use it to destroy the toxic forest and reinvigorate life on the planet. Nausicaä prevents the war from annihilating humans and animals using her knowledge about flora and fauna and her empathy for all creatures. Now, we shall look at some of the specific themes and characters closely.

Spores

The princess flies over humongous clouds of spores on her white glider clad in a blue suit and wearing a gas mask. The spore clouds are juxtaposed against white clouds in the sky giving a sense of their enormous size. This is one of the first scenes where we see Nausicaä traversing over a land colonized by what looks like an army of fungi killing organic life as we know it today.

The dystopian landscape felt familiar while I read Emily Monosson’s fascinating treatise on the future of fungi called Blight: Fungi and the Coming Pandemic. Monosson has done for fungal diseases what David Quammen did for zoonotic diseases with his magnificent book Spillover.

The book begins with an eerie tale of a dark, cold cave in mountainous Vermont. It’s also the tale of a microscopic spore shaped like a caraway seed that waits on the mud floor of the cave biding its time throughout spring, waiting for the bats to return home during fall. An oblivious member of the roost sits on the floor lapping water and the spore lodges on the bat’s membranous wing. It germinates, sprouts hyphal strands in the bat’s brown wings, reproduces when the time comes, and sends thousands of spores in the air. The bat doesn’t survive. Most infected bats will die but not all and the cycle continues. The spore belongs to a fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans which causes white-nose syndrome and has killed millions of bats since the 2000s.

We live in a ubiquitous invisible cloud of fungal spores. They are everywhere including the radioactive ruins of Chernobyl and the International Space Station. The nebulous sporedome might not be as visible and opaque as the one Nausicaä flies over but they are omnipresent and constantly edging towards being pathogenic owing to rising temperatures, antibiotic overuse and antibiotic resistance, and illegal animal trade across the globe. Sounds familiar? It’s (only) been four years.

Monosson also captures the fate of frogs going extinct due to a curious fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), a chytrid fungus, a member of the Chytridiomycota, a division that diverged early from the fungal tree and kept their tail-like appendage making them mobile and full of agency. Usually, they feed on the dead but some like the Bd parasitize the living, sending root-like appendages on the host skin, in this instance the smooth, mucilaginous, keratin-rich frog skin, cloning itself until it forms a bulbous head with roots sprouting from it called a zoosporangium, filled with tailed spores (sporangia) which are released in the atmosphere.

Frog skin is a splendid organ. It is permeable to oxygen, the mucilage in the skin is a complex microbiome, and regulates electrolytes necessary for neural function. The whole The Last of Us-like infection event leaves the frog’s skin in tatters (one can only imagine), cuts off oxygen and electrolytes, and results in its death in a cardiac arrest-like event.

Deep breaths. My readers know how much I love frogs.

Since its discovery in 1998 by Professor Lee Berger, the disease Chytridiomycosis caused by Bd has been the cause of death in many amphibians. The most recent global, quantitative assessment of the amphibian chytridiomycosis panzootic (term for the pandemic equivalent for animals) reported the decline of at least 501 amphibian species over the past half-century, including 90 presumed extinctions. The authors concluded that the chytridiomycosis panzootic represents the greatest recorded loss of biodiversity attributable to a disease.

So how did Bd evolve in the first place?

The unusual African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) has been used in pregnancy tests since 1931. Here’s a bit about how a certain English endocrinologist Lancelot Hogben was experimenting on the Xenopus to test the function of pituitary hormones on frog skin. Instead, he found that exogenous injection of pituitary hormones from an ox induced ovulation in the frogs! Soon thereafter, someone figured out Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) could induce eggs in said frogs! Lo and behold, thousands of African clawed frogs were shipped around the globe in another round of transcontinental animal trade (is there no end to this?) where they were kept in captivity and when injected with urine samples from pregnant women ovulated within hours.

By the 1970s, these creatures were everywhere, kept as pets, released in the wild after captivity, or used in laboratories. I used Xenopus genes as a molecular biologist to understand ubiquitin protein function (Xenopus have been used extensively in ubiquitination studies since the early 1980s) because it provides a unique cell-free system for high-throughput biochemical studies (and I did NOT know any of this until last month!)

Finally, a study showed that the Bd fungus piggybacked on Xenopus and spread across the globe. The route is complicated because distinguishing precise pathways requires deep genetic sequencing. Xenopus that carry the Bd fungus do not get sick making them asymptomatic and as a result, potential super-spreaders. Two words we need to keep hearing now and then like a nice little inoculation lest we forget how easy it is for illegal animal trafficking to tip the scales towards a chain reaction we wouldn’t know before it is too late.

Nausicaä and her people are living in a magnified dystopian version of the fungal panzootic aftermath in the movie and it is only a glimpse of how anthropocentric activities can distort the delicate balance of nature.

Lens and Limits of Exploration

Nausicaä has just discovered an empty Ohmu shell inside the toxic forest and has harvested one of its glass eyes. The opening sequence is one of the most breathtaking scenes I have ever seen in a movie. Every frame is a tribute to contemplation and consideration about our relationship to the world. Nausicaä lifts the glass eye, holds it above her head and watches the spores drift like winter’s first snowfall. She crawls under the eye and lies on top of the Ohmu staring at the galaxy of spores. Almost like an astronaut watching the cold and sterile space from the window of a spaceship.

Both zero gravity and toxic spores induce dual emotions of fear and awe. The eye becomes the lens to witness the world around us; too short-sighted and we perceive the cold and sterile worlds as dangerous and unlivable, but with ample insight the blue-grey cavern becomes a place of beauty and reconciliation with a world whose secrets are yet to be revealed.

Nausicaä, like every inquisitive explorer/pioneer in our world, is unafraid to reach beyond that layer of protective glass. She differs from them because her intentions are not colored with expansionist intentions but remain academic even though she does use a charge of explosives to dislodge the glass eye. She is after all harvesting the eye for her people to make things from the glass. The scientific wonder turned into an industrial aim. This whole sequence reminded me of the intrusive nature of scientific exploration. It’s necessary but sustainable only if the demands can cope with the availability of resources. It only took a few hundred research projects to spearhead enterprises like deep-sea mining for rare earth metals. How do we minimize the fallout? How much do we tinker before we are removed from scientific exploration and get cosy with industrial extraction?

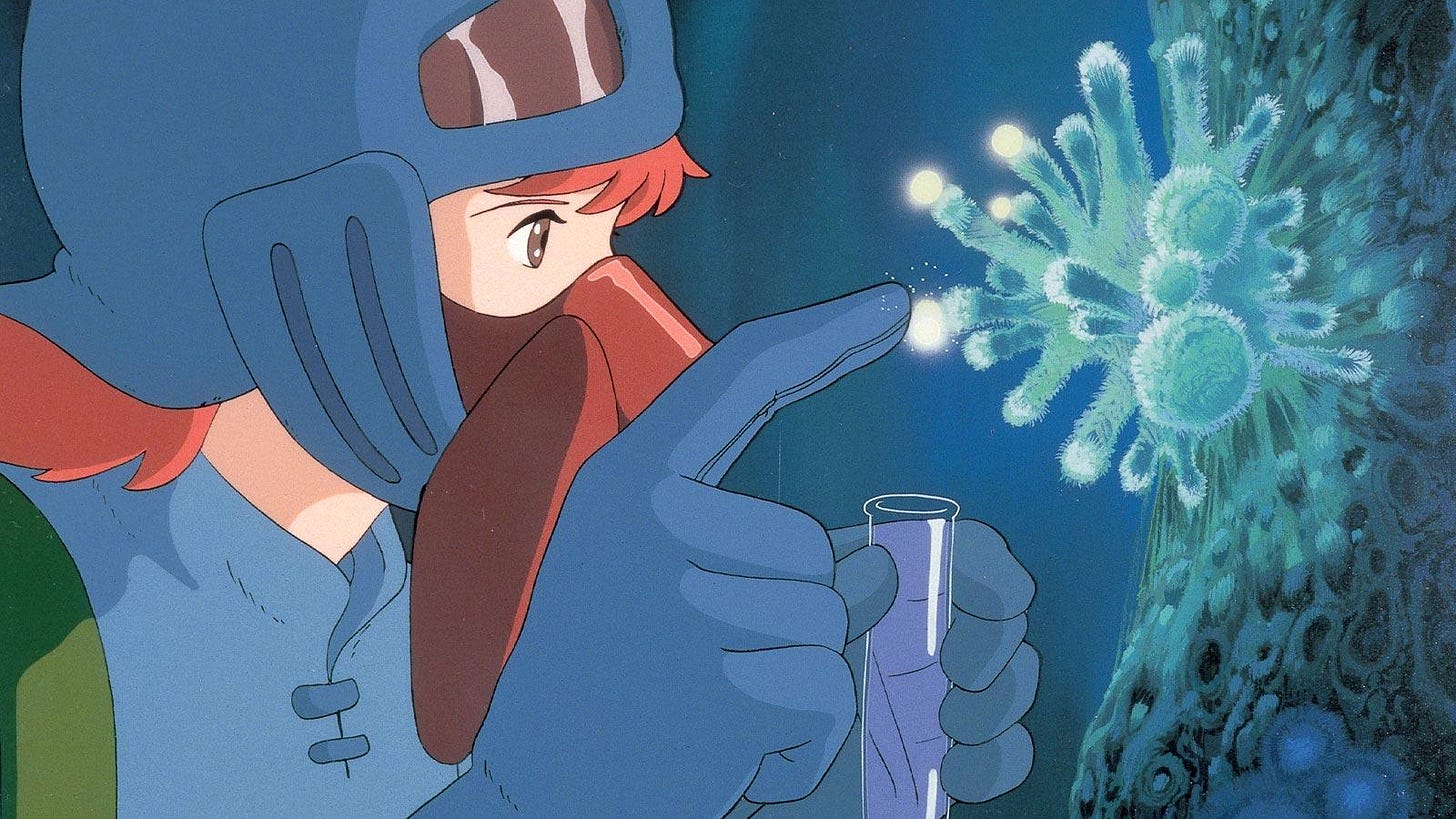

Nausicaä: The Experimentalist

She taps luminescent spores from a sprouting body lodged in a trunk into a glass tube. A favorite scene of mine because I carry tiny sample bags with me everywhere in case I come across an interesting feather, leaf, or pieces of broken bird nests that I would collect. And of course, she never removes her gloves. Being gloved and masked at all times of first contact is something that I particularly loved about this movie; the due diligence in these scenes I believe helped garner a scholarly interest in Nausicaä. Later we find that she has been growing plants from the toxic jungle in the basement. She discovers that they are not poisonous at all if grown in clean soil and water; she uses water from the deep wells that the rest of humanity is using. A classic case of bioaccumulation. The plants have been soaking the poison from the topsoil and maintaining clean freshwater reserves deep underground.

This summer, I went to the local grocery shop and found a lady asking for a lump of alum. She told us the groundwater has to be filtered more frequently these days than in previous years. The freshwater level is low in the downtown suburbs around Calcutta. Summers are longer and harsher and the ground remains parched for long spells. The regenerative powers of water have been a common theme in many Ghibli movies, particularly in Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001). A spiritual extrapolation shows the influence of Shinto, Japanese Buddhism, and Shugendō mountain asceticism in these narratives. Water and its role as a purifier has twofold significance: material and spiritual. A life-giving, cleansing, and energizing material element on one hand and spiritual transformation and healing on the other. The physical gesture of ablution is an important rite and a habit for the people of my country. But the same people still have to use alum to purify drinking water.

Monstrous Fauna

I have immense love for Arthropods and especially, trilobites. And Ohmus resemble the extinct marine arthropods that first appeared in the Early Cambrian (521 mya). In the movie, Ohmus are colossal creatures with tough exoskeletons divided into articulated segments which they shed during their growth cycle. Although, the largest partial specimen of an Ordovician trilobite Hungioides bohemicus discovered in 2009 is estimated to be 86.5 cm long making them smaller than the fictional Ohmus. Visually, they remind me of sandworms, the protectors of the mind-enhancing drug spice in Frank Herbert’s Dune. Similarly, the Ohmus are keeping the toxic jungle at bay and protecting the humans which is revealed towards the end of the movie cementing their larger role in the ecosystem.

We already saw Nausicaä harvesting an Ohmu eye lens. Even the earliest trilobites had complex eyes confirming that arthropod eyes and the eyes of other animals evolved much before the Cambrian. Lenses of trilobite eyes were made of calcite (CaCO3) and pure forms of calcite are transparent making Ohmu eye lens pretty believable. Fans can only extrapolate!

But imagine resting on a mudflat in an Ordovician forest on a sunny morning watching giant trilobites roam around with thick rigid calcite lenses designed to provide stunning depth of field in vision and remove spherical aberration (unlike squishy human eye lens) according to the optical principles that will be discovered by Descartes and Huygens in the 17th century in the future. Phew!

The God Warrior that fell out of the Tolmekian ship is brought inside the castle in the Valley and is being readied for war. It looks like a malignant cancerous mass, pulsating and throbbing enmeshed in giant capillaries, constantly pumped with biofuels for incremental growth. To what degree is biological enhancement sustainable in the case of agriculture or animal production? To what degree is plying antibiotics for pig production across the planet coming down to bite our backside? The God Warrior is a biological weapon and Miyazaki never shies away from presenting the dangerous forces of nature even if they have a biotechnological origin.

The above scene always reminds me of Saruman salivating at Isengard in the western part of Middle-earth (analogy alert: warring factions arriving from the West in many fictional universes is surely a coincidence). Moreover, fueling and revitalizing The God Warrior seems much like breeding orcs in the deep underground pits. My penchant for finding Tolkien references everywhere might be whimsical but stories have a way of concatenating together in my head.

More elements will be analyzed in Part II of this long essay. Until then feel free to share your thoughts about the movie and if you have not watched it, I hope you will for the sake of my beloved frogs.

![[Nausicaa-First-Appearance.jpg] [Nausicaa-First-Appearance.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Iikf!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd84e55d9-547b-46c5-8985-601b99bf9821_1280x692.jpeg)

![[Nausicaa-Rescuing-Yupa-from-Ohm1.jpg] [Nausicaa-Rescuing-Yupa-from-Ohm1.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9brf!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F88d8095d-bc1d-4e2e-b8a3-f8160fb5c7fb_1280x692.jpeg)

![[Nausicaa-Gestating-Giant-Warrior.jpg] [Nausicaa-Gestating-Giant-Warrior.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!byuR!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3269b3b5-7dbf-4933-9ecf-615a0cf711b4_1280x693.jpeg)

So, I'm not a fan of frogs, but I might have to give this movie a go after your essay :)

Wwooooow