On the Resurgence of Psychoanalysis

Four contemporary books on psychoanalysis and its everlasting shadow on our culture

Ah, to have a phenomenon named after you: Newtonian, Darwinian, Machiavellian, Lamarckian, Brownian. However, to have your names become synonymous with entire psychoanalytical oeuvres is truly remarkable: Lacanian, Freudian, Jungian.

Google's Ngram is a valuable tool for tracking how ideas, in terms of words and phrases, have circulated in printed texts throughout history since the 1800s. During the countercultural boom of the 1960s, Freud's influence was widespread. Lacan maintained a consistent presence from 1990 to 2010, while Jungian concepts had a marked presence from the 1980s to the early 2000s. However, all three figures have seen a notable decline in popularity since the 2010s, particularly Freud, who became less popular in the 1980s. This just gives us an idea about their presence in the written word and not in other forms of media.

So, why is this essay focusing on the resurgence of psychoanalytic practice if Freud, the "old man with the stare and the pipe," is considered out of fashion? Is he really out of style though? Anthony Hopkins portrayed Freud in a recent film. His influence still lingers in popular culture, like a Warhol soup can print or a Marilyn Monroe pinup poster. Jung continues to live in fields such as philosophy of sciences and tarot reading.

Setting aside my interest in cognition and psychology, I am curious to see how serious practitioners of psychoanalysis, artists, and thinkers have adapted or modified the original ideas to suit our modern world. Since 2020, with the surge of online therapists, therapy has become more democratized and prevalent in social discussions albeit with the side-effect of “therapy-speak” which is also pronounced in urban circles. However, psychoanalysis has not followed this trend. Freud himself recognized the limitations of psychotherapy, understanding that it was primarily accessible to the European middle class during his time. After World War I, the Free Clinic Movement emerged in 1918, leading to the establishment of numerous cooperative mental health clinics across Europe during the 1920s. Freud later acknowledged that psychoanalysis could play a significant role in advancing social justice.

The early 20th-century psychoanalysts saw a future of the practice outside the confines of the Viennese bourgeoisie and their gendered and sexual psychic ailments. Despite this, psychoanalysis refused to cross the racial and class structures of its Freudian period, a pattern that persists today. Who has the money and the right to have their dreams mapped, collated, and interpreted for a better inner life? Not all of us.

I believe there is still hope. With reliable books and insightful thinkers, we can uncover new aspects of our existence through psychoanalysis. Gain some insight from old ideas and instill them in our screen-abled minds. I have four works by remarkable creators who offer fresh perspectives in psychoanalysis.

I used to be an avid reader of the Dr. Max Liebermann series of books by Frank Tallis, the clinical psychologist and writer. The first book, A Death in Vienna was set in the time of Freud, Klimt, and Mahler. A closed room murder solved by Detective Oskar Rheinhardt and Max Liebermann, practitioner of the controversial new science of psychoanalysis. As period novels, they are exquisite with historical details right down to the musical scene and political background during the Habsburg monarchy. But the book I love the most is his nonfiction book The Act of Living: What the Great Psychologists Can Teach Us About Finding Fulfillment.

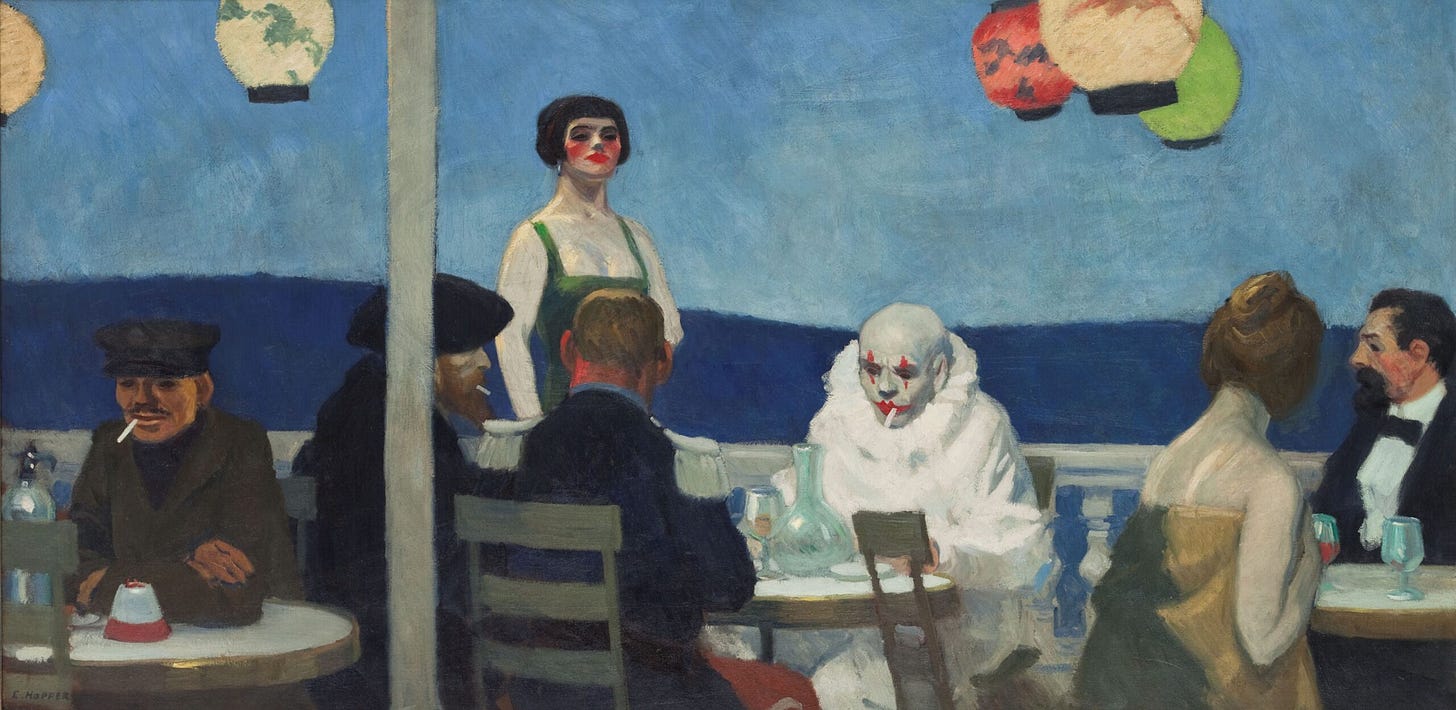

Tallis celebrates the intellectual history and legacy of psychoanalysis via lives of lesser-known figures like Fritz Perls, Abraham Maslow, Otto Rank, Arthur Janov, and Donald Winnicott. Each chapter is dedicated to a particular aspect of human psyche like identity, sex, narcissism, adversity, security, etc. and weaves both old and new research in psychology and neuroscience. It’s a dense book which works as a serious introduction to psychoanalysis but not overpowered with dry facts. In fact, this book begins and ends with many Edward Hopper paintings and their psychological interpretations.

“Psychoanalysis is about what two people can say to each other if they agree not to have sex.” - Adam Phillips

Begins one of the most difficult books in terms of its language and subject matter that I have read this year. Intimacies by Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips is a book about the possibilities of human intimacy departing from traditional psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic exchange being a non-sexual intimate exchange is discussed using Patrice Leconte’s 2003 film Confidences trop intimes (translated as Intimate Strangers) where a woman mistakes an accountant for her analyst and keeps returning back to have conversations with him. These untruthful yet fulfilling nonsexual conversations leads to an unusual psychoanalytical setting. In the second chapter, authors discuss the radical practice of barebacking as an intimacy that rejects the personal in gay culture and other aspects of queer psychology.

The third chapter is my favorite of the four. Serial killers like Jeffrey Dahmer and genocide mongering politicians are featured while the authors discuss the use of aggression to gratify ego. Speaking about the Bush administration, they write,

We live in a period dominated by what Laplanche has called the psychotic enclaves of good and evil. Imagine: a group of men, having manipulated the political system of the most powerful country in the world so that their presidential candidate is declared the winner of an election he in fact lost, interpret this thuggery on their part as a mandate to go to war. The 9/11 terrorist killing of nearly three thousand people— a tragic but modest number compared to the tens of thousands of Iraqis slaughtered by the American military machine, Iraqis who had nothing whatever to do with 9/11 was, as many others have pointed out, eagerly seized upon as providing the moral justification for an imperialist takeover of a Middle Eastern country.

As I write this, I pause to reflect the significance of this excerpt from the book. Equating cold-blooded serial killers with fascist regimes brings us to more questions like,

[…] do we have any way to understand this behavior? Psychoanalyzing collectivities is, as Freud warned in Civilization and Its Discontents, a risky enterprise. Where, exactly, is the collective or governmental psyche that corresponds to the individual psyche?

In a sense, how do we understand voters? The authors turn to Foucault for answers. According to Foucault, power aims to produce subjects defined (and, correlatively, made visible and controlled by imperialists and their various machinations) by particular desires. We know that desires are visible, quantifiable, and prone to acquiescence.

The imperialist project of invading and appropriating foreign territories corresponds to what Freud calls “nonsexual sadism” in the 1915 essay “Instincts and Their Vicissitudes,” which he defines as “the exercise of violence or power upon some other person or object,” the attempted mastery over the external world.

The obscure academic language might be a hindrance for the uninitiated like me, some of the paragraphs are literally mental acrobatics, but Bersani and Phillips present a completely new way of looking at depravities as well as intimacies of human psyche which was enough for me to hurt my brain.

Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? is her magnum opus for me. A ridiculously talented artist, Bechdel has pushed the boundaries of graphical representation, memoir-within-a-memoir, and juxtaposition of first-person narrative with epistemological concerns where texts and graphics seamlessly coexist. And this is just the beginning of the layers of magic that lies inside this book. The book has maps, memories, psychoanalytical texts, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, and Bechdel’s life as she works on the book. A metabook. A metaessay.

She is exploring herself in the present as well as her mother through her past memories of family, therapy sessions, and romantic relationships while simultaneously close reading great thinkers of the past. No linear narrative. No throughline. Something like our consciousness. Loop within a loop. It sounds impossible but Bechdel somehow did it.

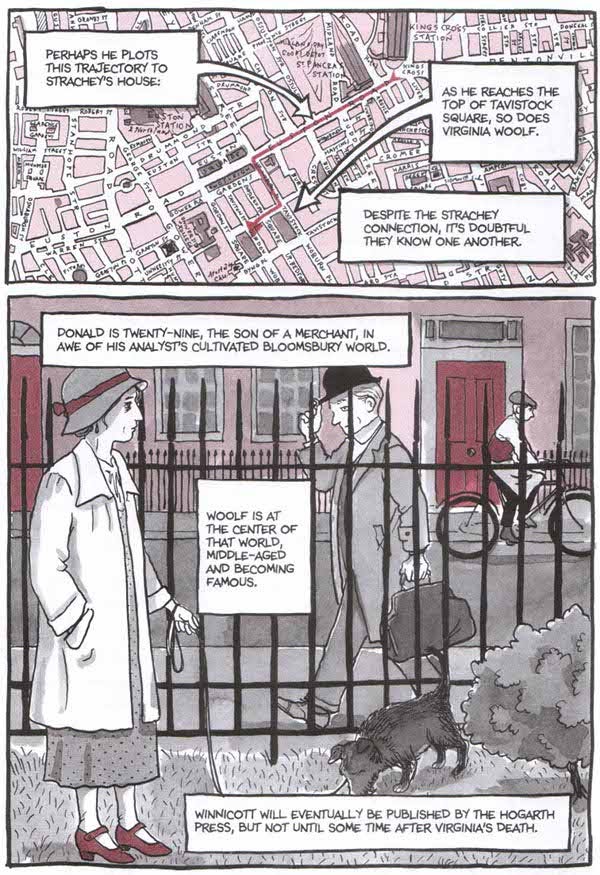

Sometimes words do a very poor job of explaining these creative expressions so here are few examples. A speculative map illustration of Donald Winnicott and Virginia Woolf meeting at Tavistock Square.

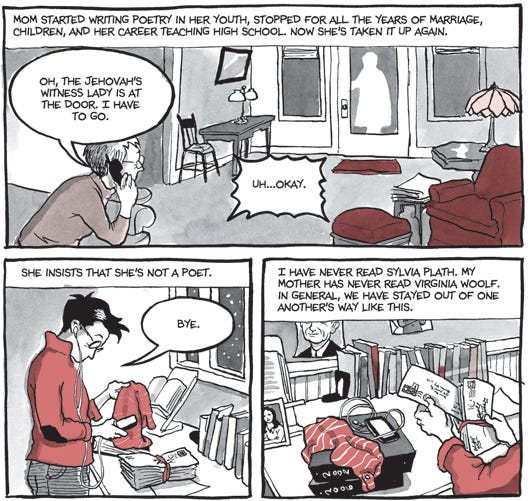

The map is followed by two more pages. One with simple panels where Bechdel and her mother are on the phone.

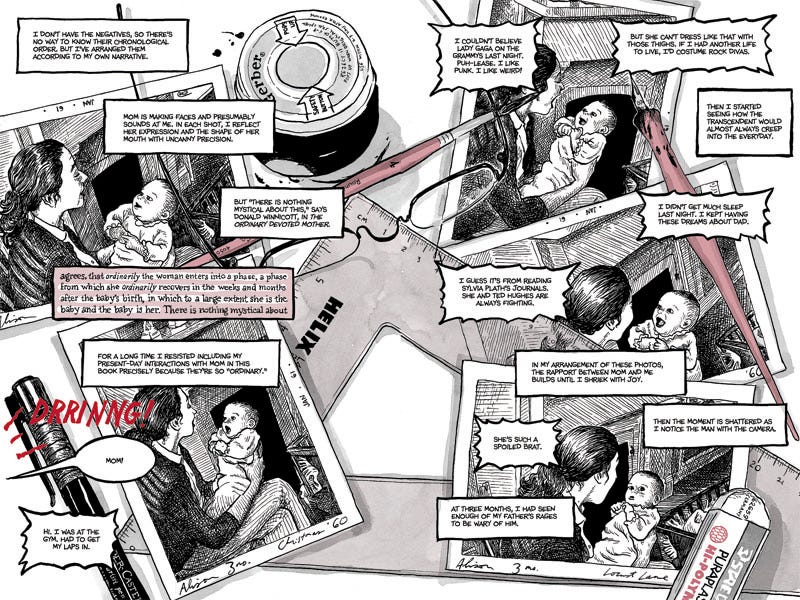

The other a dizzying array of polaroids laid out on the table while the phone rings in the background as seen by the red-inked “dringg” and mother and daughter are discussing Plath while Bechdel looks at her childhood photographs. An incredible feat. I think there is so much to learn for those interested in comic books, graphic design, psychoanalysis, storytelling, and essaying.

Tina Richardson is a psychogeographer and cultural theorist from the UK. Tina and I met on Instagram when I shared my copy of Borges on the feed. She kindly sent me her unique booklet or as I like to call it the “dream-zine.” On Waking and Walking is an experimental poetry and prose booklet for those interested in philosophy, psychogeography, walking, psychoanalysis, and dreams. The most interesting piece in the booklet is an imaginary meeting and conversation between Fenella Brandenburg, Jorges Luis Borges, and Jean Baudrillard. It is about maps, geography, and human psyche. The Psychogeographer’s Mantra is a poem for walkers and dreamers alike hinting at ways to chart and map courses in a world of devices and numbers. I welcome readers to visit Tina’s website if they are interested in the booklet.

Thanks to Tina, I learnt something about psychogeography, something I hadn’t heard before. For an introduction, read this blog post on the MIT Press Reader. The term psychogeography was first used by members of the Lettrist International, a Paris-based collective of radical artists and cultural theorists that was active in the early 1950s. They described it as “a science of relations and ambiances” or a new way of looking at a city or a place, adding soul to the soil under our feet. Guy-Ernest Debord, a French Marxist theorist, philosopher, and filmmaker proposed one of psychogeography’s first genealogies. Some of the names on his list of people (few more amusing than the rest) who explored the psychological geographies of their work were:

Piranesi is psycho-geographical in the stairway.

Jack the Ripper is probably psycho-geographical in love.

Andre Breton is naively psycho-geographical in encounters.

Évariste Galois in mathematics.

Edgar Allan Poe in landscape.

Later, many thinkers and writers made a list of psychogeographers who elevated the psychological measures of wandering and walking.

“On Saturday evenings,” wrote opium-eater and peripatetic Thomas de Quincey, “I have had the custom, after taking my opium, of wandering quite far, without worrying about the route or the distance.”

As a lover of lists and list makers themselves, I started a list of my psychogeographers and came up with one name: Gaston Bachelard. Having read only his Poetics of Space and knowing little about his work in the psychology of sciences, I find Bachelard a candidate for the psychogeographer of the scientific mind. A final book that covers Bachelard’s lesser-known works in the anglophone world is given below.

I have more questions and unread books as I finish this essay and the never-ending curiosity about my own mind as well as collective psyche of our society. By now, we have left Freud’s shadow (pun intended?) and stretched out to new possibilities of the legacy of psychoanalysis. Our desires and despairs remain agonizingly foreign to most of us, leaping out of the cauldrons of our minds. But creative arts, experimental writing, and psychological research can help us answer these questions. Maybe these books can lend you a raft or two while we are floating in these unknown seas.