On the quiet charm of monastic life

Every undergraduate in a genetics class is taught about Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884). Augustinian friar and abbot in now Brno, Czech Republic. I have always imagined the friar in his starched habit, poring over his beloved pea plants, and making tidy notes in his journal. He tested some 28,000 (!) plants over seven years. Scientific experiments took a ginormous amount of time in the 19th century. But a monk engaged in such an endeavor was rare. What drove him to accomplish such a monotonous task? Was it the discipline? The solitude? Derived from the Greek root μόνος (monos) meaning ‘alone’, monasticism is a quaint concept for many of us. What can a life of self-denial have any possible meaning for us?

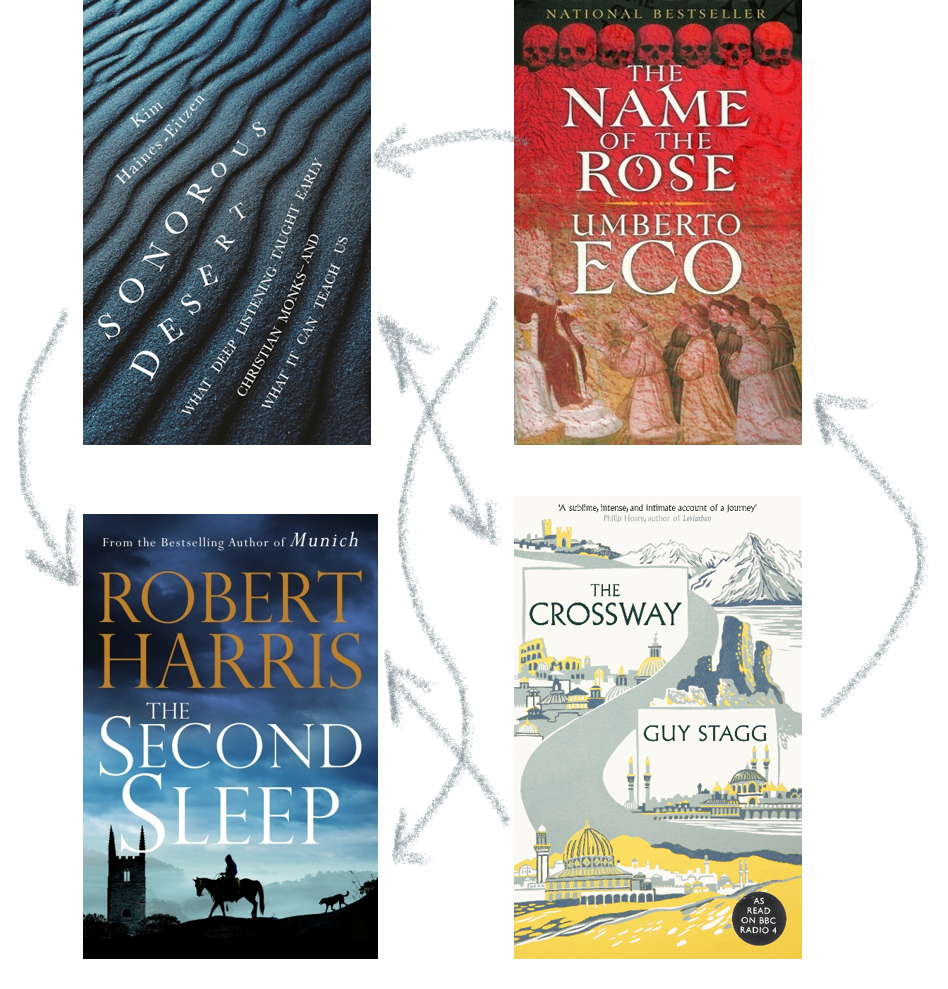

In recent years I have come to appreciate the literary and scientific roles of monks. They were the earliest translators and librarians. Copying Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Sanskrit texts and translating them. Gutenberg would have to wait for his spotlight. The following books show various facets of this quiet yet stimulating life.

In Sonorous Desert, Kim Haines-Eitzen travels to the deserts of North America and Israel to record the sounds of desert landscapes. Drawing from the lives of communal monks and hermits and ancient texts she presents a reverberant picture of solitude and slowing down. The desert is at once a space of cacophony and silence. Just like our minds. Enjoy a recording below from the book. Find more such recordings here.

The Second Sleep by Robert Harris follows a medieval priest trundling through the muddy tracks to investigate a death in a village in Wessex, England. There was a medieval practice of waking up in the night for prayer or contemplation and going back to sleep again. Harris, the master plotter, writes a scene where the priest wakes up at night and discovers a black, shiny, obsidian slab with a half-eaten apple engraved on it: the original sin. You realize this isn’t the 15th century but a post-apocalyptic world where technology has wiped out the past leaving iPhones scattered around like fossils. A powerful book about the tightrope walk of our digital lives.

Digital burnout is felt by most of us. We switch off our phones. Go for runs. Meditate. But then come back to look for answers on our phones. This omnipresent anxiety is revealed in a deeply personal memoir titled The Crossway by Guy Stagg. He walks from Canterbury to Jerusalem. A non-believer takes a pilgrimage looking for answers. His cross-country walk is frugal, mainly depending on strangers, parishes, and local churches for food and shelter. Something about meeting people on the road presents a possible antidote here: Less is more.

The uber-text of all intellectual historical fiction for me is The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco. William of Baskerville, the Franciscan friar. I have a longstanding crush on his playful agnostic interpretations (never heretical), acumen, and Holmesian talents. Murder in a monastery. Poisonous herbs. Translation of texts. Latin jibber-jabber. For the uninitiated, John Turturro plays the titular role in a 2019 miniseries.

I leave you with a cinematic thought. In the movie Interstellar (2014), the protagonist Cooper listens to a sound recording of rain in the spaceship. In the vast outer space, astronauts come closest to experiencing solitude unlike any. Not so different from a monk’s life.

Arrivederci!